The Digital Strain of Modern Work

In the span of a single generation, the human visual system has been forced to adapt to a radical change. For thousands of years, our eyes were designed for “distance viewing”—scanning the horizon, tracking movement, and navigating 3D spaces in natural light. Today, the average professional spends ten to twelve hours a day staring at a glowing, 2D plane just twenty inches from their face.

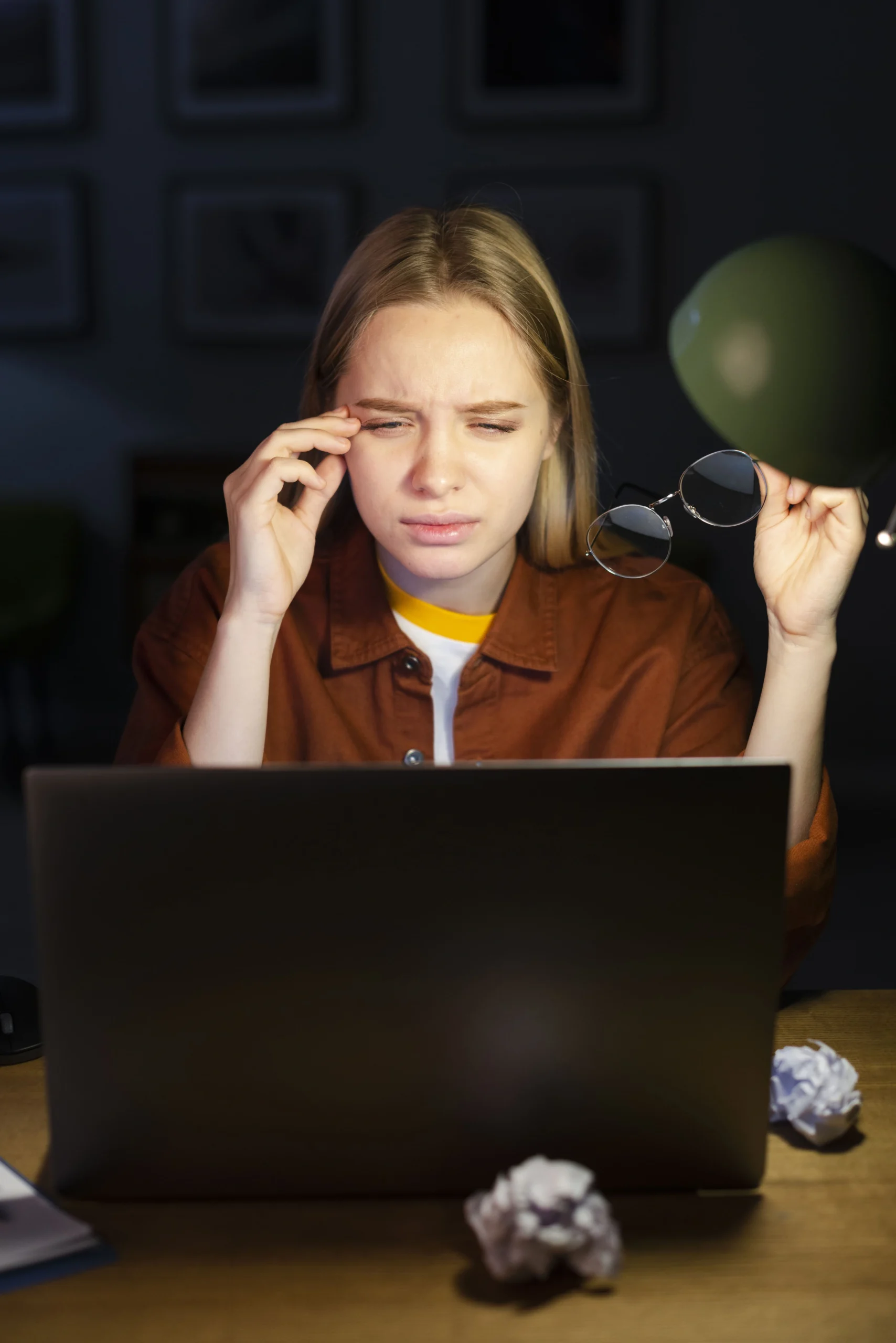

This shift has led to a widespread phenomenon known as Digital Eye Strain (DES), or Computer Vision Syndrome. If you’ve ever ended a workday with blurry vision, dry eyes, or a dull ache behind your forehead, you’ve experienced it. While these symptoms are often dismissed as “just part of the job,” they are actually signs of significant physiological stress on the delicate muscles and nerves that control our vision.

In this article, we will examine what the latest research tells us about why screens are so taxing, debunk some common myths about blue light, and provide a set of evidence-based strategies to protect your vision in an increasingly digital world.

The Mechanics of Focus: Why Screens are Different

To understand eye fatigue, we have to look at how the eye focuses. To see something close up, the tiny ciliary muscles inside your eye must contract to change the shape of the lens. This is an active, energy-consuming process. When you stare at a screen for hours, these muscles are essentially held in a state of constant contraction—the ocular equivalent of holding a heavy dumbbell at arm’s length for eight hours.

Furthermore, screens are composed of “pixels”—thousands of tiny dots with blurred edges. Unlike a printed page, which has sharp, high-contrast edges, digital text is harder for the eye to lock onto. This causes the eye to constantly “search” for a clear focus point, a process called “accommodative lag.” This micro-oscillation of the eye muscles is a primary driver of fatigue.

Another critical factor is our blink rate. Normally, humans blink about 15 to 20 times per minute. This keeps the surface of the eye (the cornea) lubricated. However, studies show that when we look at screens, our blink rate drops by up to 60%. We also tend to perform “incomplete blinks,” where the lids don’t meet fully. This leads to dry, gritty eyes and “burning” sensations by the end of the day.

The Blue Light Debate: Fact vs. Fiction

In recent years, “blue light” has been blamed for everything from permanent eye damage to chronic insomnia. This has spawned a multi-million dollar industry for blue-light-blocking glasses. However, the scientific consensus is more nuanced than the marketing suggests.

The amount of blue light coming from a computer monitor or smartphone is actually a tiny fraction of what we get from the sun on a cloudy day. There is currently no evidence that the blue light from digital devices causes “retinal damage” or physical eye disease. The real reason blue-light glasses sometimes make people feel better is often due to a slight tint that reduces overall screen glare, not necessarily because they are blocking “harmful” rays.

The primary issue with blue light is its timing. Blue light is a “daytime” signal; it suppresses melatonin and tells our brain to stay alert. Using screens late at night confuses our circadian rhythm, making it harder to fall into restorative sleep. The “fatigue” we feel from blue light is often actually the result of systemic tiredness caused by poor sleep quality, rather than direct damage to the eyes.

Screen Position and Ergonomics

One of the most overlooked causes of eye strain is the physical setup of our workspace. Many people have their monitors too high, too low, or at an angle that causes glare. If your monitor is too high, you have to open your eyes wider to see it, which increases the surface area exposed to the air and speeds up the evaporation of tears.

The ideal position for a screen is about 20 to 28 inches away from your face (roughly arm’s length), with the center of the screen about 15 to 20 degrees below your horizontal eye level. This allow the eyes to rest in a more “natural” downward gaze and minimizes the strain on the neck and shoulder muscles.

Lighting also plays a major role. If the room is too dark, the high contrast of the screen causes strain. If the room is too bright, or if there is a window directly behind you, the resulting glare on the screen forces your eyes to work harder to see the content. Aim for “balanced” lighting where the brightness of your surroundings roughly matches the brightness of your screen.

The 20-20-20 Rule and Beyond

The most effective, research-backed strategy for reducing digital eye strain is the “20-20-20 Rule.” For every 20 minutes of screen time, you should look at something 20 feet away for at least 20 seconds. This simple act allows the ciliary muscles to fully relax and reset their “focal point.”

However, we can go further than just looking away. “Palming”—covering your closed eyes with the warm palms of your hands for a minute—can provide deep relaxation to the optic nerve. It creates a state of total darkness and warmth that allows the eyes to recover from the high-intensity light of the screen.

Using “artificial tears” or lubricating eye drops can also be highly effective, especially in air-conditioned offices where the air is dry. By proactively lubricating the eye before the “gritty” feeling starts, you prevent the inflammation that leads to redness and irritation at the end of the day.

Practical Insights: Optimizing Your Digital Environment

Beyond behavioral changes, there are several technical adjustments you can make to your devices to ease the burden on your eyes. First, increase the text size. If you are leaning forward to read small fonts, you are increasing the strain on your eyes and your back. Use the “zoom” function on your browser to make reading effortless.

Adjust the “color temperature” of your screen. Most modern operating systems have a “Night Shift” or “Night Light” mode. By shifting the screen toward the warmer (yellow/orange) end of the spectrum, you reduce the “harshness” of the light, which many people find significantly more comfortable for long-term reading, regardless of the time of day.

Finally, consider your “screen breaks” carefully. If you take a break from your computer by looking at your phone, you haven’t actually given your eyes a break. A true visual break involves looking at the 3D world, moving your body, and allowing your eyes to perceive depth and natural light.

Preserving Your Vision in a Digital Age

We cannot escape the digital world, but we can learn to navigate it with more awareness. Eye fatigue is not an inevitable consequence of using computers; it is a sign of “visual overuse” that can be managed with the right habits and environment.

By understanding the mechanics of how we focus and the importance of lubrication and rest, you can significantly reduce the discomfort of digital work. Protecting your eyes today ensures that you maintain the visual clarity and comfort needed for a long, productive career. In a world that demands our constant attention, your vision is one of your most valuable assets—treat it with the care it deserves.